Photographers are crucial to any underground music scene. “Only a rare eye can make such intense people doing intense things on sticky floors so unforgettable, even decades later,” said Jello Biafra, speaking of those like Ed Colver and Glen E. Friedman, those who braved the violence of the pit to capture the California punk explosion, and whose images still remain embedded in the hearts and minds of diehards and true believers.

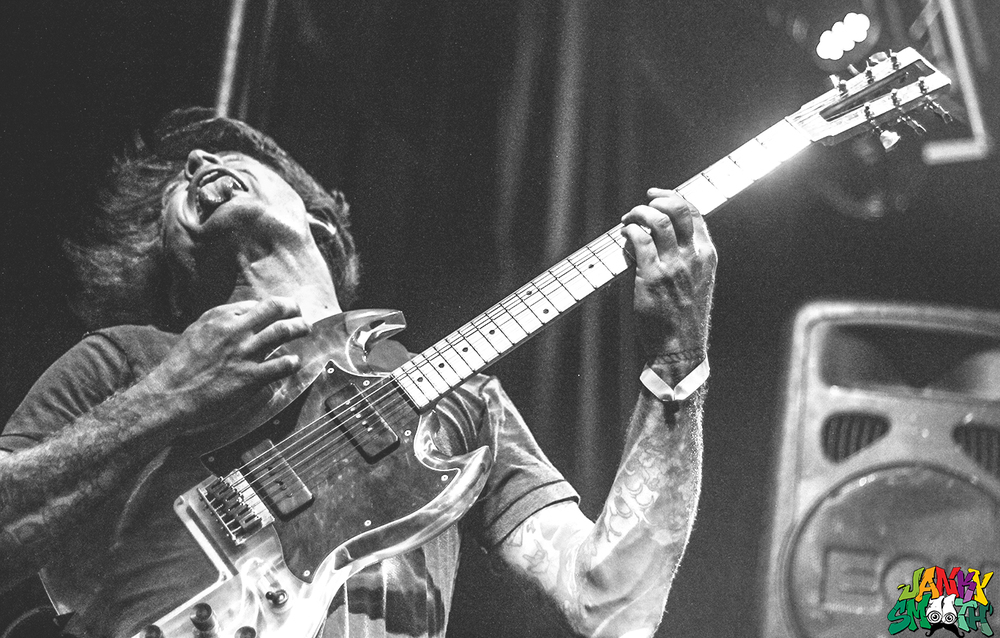

People someday may be saying the same about David Evanko, aka Minivan Photography, who has snapped every band across the fuzzy spectrum (you’ve definitely caught some of his work here on Janky Smooth) with a cool intimacy that not only puts you there, but makes you feel what there was like. His work has done nothing short of elating the local scene, so much so that you sense his spry, exploratory lens extends far beyond the walls of sweaty basements and hyped music fests.

Before embarking on a recent South American odyssey, he was shooting up to four shows a week, driving up to L.A. as often as he could from his east San Diego barrio—a city that’s been a big, fat music void for far too long. Eventually, he recognized the restlessness itching at the back of his mind—he was ready to seek more.

“I was getting kind of stale, I guess. Doing the same shit every night,” he told me, pushing his long sun-bleached hair out of his eyes. “As awesome as it is—shooting awesome shows—it’s eventually going to get old. And it wasn’t that it was getting old, but it felt like I was just repeating myself. I feel like in order to grow as an artist, or mostly as an individual, you have to get out of your comfort zone. There’s so much to see.”

He decided to start working with Give and Surf, a non-profit dedicated to building schools and basic infrastructure for the indigenous and impoverished Ngobe populations in the Panama islands. “The opportunity was there, so I took it.”

I sat down with David at Two Boots in Echo Park and over some slices of Tony Clifton pizza, we talked about his temporary escape from the hustling American bubble to the remote Isla Bastimentos; all the amazing things Give and Surf does for the indigenous people there; how the tourism industry is actually killing the local culture and ecosystem; what’s in store for the future of Minivan; and even the upcoming election (because why not).

Brent Smith: How long were you on this trip?

David Evanko: I lived down in Panama for a two months, living as simply as possible. You don’t have access to certain foods. Part of the island doesn’t even have electricity. They depend on the rain water.

BS: Lots of down time?

DE: I pretty much went fishing every day, hung out with the kids I was working with, and surfed. I wanted to expand my photography into something I wasn’t familiar with.

BS: What are those kids facing?

DE: They basically have no glimmer of hope when it comes to acquiring any kind of career, or getting an education past middle school. These kids are just stuck on an island. They just stop going to school once they reach middle school, and they go work in construction, or they work for this fancy resort on the island.

BS: Which would seem like a good thing, having a resort on the island.

DE: The people who own that resort have pretty much fucked them all over, and their entire village is trapped in that career line for their whole lives—until the resort is gone and something else happens. So the non-profit takes in these indigenous children, gives them an education and scholarship opportunities. A big project we were working on when I was down there was raising money for a boat that would pick them up and actually take them to the high school on the other island. They just don’t have the resources.

BS: Even for something as basic as the equivalent of a school bus driver.

DE: The shitty thing is they’ve grown to be okay with it, and the construction jobs on that island allow them to be okay with it. So if one of those kids has a dream of becoming a scientist or whatever, anything outside of construction or farming, they’re out of luck. There’s just no hope in it.

BS: Where did these jobs come from?

DE: Basically, Americans went down there about ten years ago, went to the leader of the [Ngobe] tribe, and basically said, give us this land for $100K, something really cheap, and we’ll give you power, water, houses, jobs for you and your kids for the rest of your lives. The tribe agreed. And so the gringos went in, took the land, and built this fancy, amazing resort, it’s huge. They also created two little villages, one’s called Bahia Roja and the other is called Bahia Honda, and that’s where the natives have lived, walking to work and building this resort. But after ten years, the gringos didn’t come through on any of their promises. They still have no water, no electricity. One of the villages has 10 houses for 150 people, you do the math. They all have kids they have to look after too, and they’re just getting screwed while this resort takes more and more land. They now even want the land that we’ve built the schools on so they can add another marina. They’re super money-hungry and it’s fucked up, because when you sit in the middle of Bahia Rojo, you look out into the marina and there’s multi-million dollar yachts just hanging out. Meanwhile, there are kids with no shoes and who have to wait until it rains to get a glass of water.

BS: What’s the name of the resort?

DE: It’s called Red Frog, and it’s on Red Frog Beach. There’s actually a documentary about it on how they’re fucking up the ecosystem. The reason it’s called Red Frog  beach is because this species of red frog lives on the island, and it’s only place in the world they’re found. The population has decreased something like 70% since they built that resort. They either don’t know what they’re doing, or they don’t care.

beach is because this species of red frog lives on the island, and it’s only place in the world they’re found. The population has decreased something like 70% since they built that resort. They either don’t know what they’re doing, or they don’t care.

BS: What kinds of things were you doing with the kids?

DE: [Give and Surf] received a donation of a bunch of cameras, and so they hit me up and asked if I’d like to start a photography program and teach these kids to take photos and use cameras. I said, absolutely.

BS: How did the kids respond?

DE: They freaked out, loved it. They had an awesome time.

BS: How were they different from kids here in the States?

DE: They’re really not that much different, they’re still kids—just way more bad ass because they grew up in the jungle. They can sprint across gravel barefoot and go fishing, and do things I could never do when I was 10. They’re definitely adapted to that simple lifestyle, one thing I loved is that they weren’t buried in phones. All they wanted to do was just be outside. They were the sweetest kids I’ve ever met, and the sweetest parents, amazing people, really kind.

BS: Were you staying in those villages with them?

DE: I was living on another side of the island, and there’s a different group of people that live there, they’re more of a Caribbean culture. I lived with the mayor’s brother, so I got to talk to him every day. My job over there was to get this newly-built community center up and running that was built by an outside charity, with a skate ramp and a full playground with a soccer field behind it. I basically had to do things like get a calendar going and make sure it was going to be sustainable. The goal was to eventually hire a local to keep it running after we left, so all the money goes back into the community and not to, y’know, the gringo.

BS: So nobody had phones, were there any computers?

DE: Nobody on the island owned a computer, but we even got some of those donated too. They’re really needed for school and business purposes, so now they have access to that which is really cool.

BS: Do you want to go back?

DE: Definitely. I’m having full withdrawals. I miss it a ton.

BS: Was it a culture shock coming home?

DE: For sure, everything’s fast and obnoxious and loud over here. Basically been freaking out every day, sitting in traffic. There wasn’t one single car on the island. No roads or anything. The one town where most people live was pretty loud and energetic, there were chickens and dogs and kids everywhere. Music was always blasting, all reggae, just blasting all day, but as soon as the sun went down, it was completely silent. You have to take a boat to another island for any kind of civilization.

BS: Wake up with sunrise, go to bed with the sunset.

DE: That’s how it was every day. It was totally normal.

BS: Technology is great, but we’re probably over doing it—staying up all night under artificial light staring at a computer screen [which is exactly what I’m doing as I write this].

DE: It’s just excess at this point.

BS: Especially in L.A., where we have little excuse to not make the quick drive into the mountains or the desert.

DE: I go camping maybe once a month. I go to Joshua Tree all the time. I just need to get out of the city sometimes, and this two-month long trip was my way of just getting it all out of my system at once. But it actually made me realized how much more I love it [laughs]. It was hard to leave. I was like, man, I could just sit here the rest of my life and fish for my dinner every night.

BS: Were you good at fishing?

DE: No, I was actually pretty horrible [laughs]. But it’s so easy there because there’s so much abundance of everything. There was one spot we’d surf, where we hiked 30-40 minutes into the jungle and come out the other side to this beach, and there’s literally nothing, just the trail that leads there. I would never bring food or water because you could find a coconut, crack it open, drink the water, and eat it. You keep walking and then you’d find some jackfruit, just keep eating.

BS: I’ve never even heard of jackfruit.

DE: It’s delicious. It’s actually the base flavor of Juicy Fruit. But yeah, I didn’t have to worry about anything like that. I ate healthier, I felt healthier. They don’t have the power to freeze stuff, so everything’s fresh.

BS: So the trip was good for your body, your soul, what about your work?

DE: I got really into shooting wildlife, which is always a huge challenge, just finding them and getting the shot. The kids I was working with loved to have their photo taken because no one’s ever taken their photo before. Teaching them how to take photos and giving them a camera when they’ve never seen one was a pretty cool experience. Seeing them fall in love with it the way I did. Our class walked around the jungle taking photos and they took some really amazing ones.

BS: Really shows you how it’s not hard taking the small stuff granted.

DE: It’s healthy to remind yourself. Sure, we’re all broke and we could all be better off, but you put yourself in a situation like that you realize you have it so good, even if you’re broke. I would go to school and ask one of my kids what they had for breakfast, and they say, “nothing.” Just brutal.

BS: Was there any sense of depression or despair?

DE: No, the coolest people I’ve ever met. I’d go to their village and just hang out all day. Part of what we’d would do is run a surf-mentor program, and we got some surfboards donated and gave few of them to the kids who really wanted to learn. One of the kids is well on his way to getting a scholarship and going to school for surfing, which is great. We entered them in some contests and they got really fired up about it. When the waves were flat I would just be in the village with the kids on the beach all day with nothing and just talk about whatever. They were so stoked on everything, asking me all about California and having a cell phone. It’s crazy.

BS: Like being on different planet.

DE: Completely different planet. It’s crazy to see how they’re still happy given that they kind of know what they’re missing out on, but they really don’t care.

BS: It makes you think. Are we better off, or are they? What’s the life expectancy there?

DE: I’m not sure, I didn’t see too many elderly people, not on that part of the island at least.

BS: So what happens when someone gets sick or injured?

DE: That’s another thing. There was a situation where a woman went into labor in the middle of the night—twins—and the father didn’t have a boat, so she had the kids right there in the bedroom. He ran to a neighbor for help, and when the neighbor went over there, both of the kids were blue and the woman was unconscious. It’s about a ten-minute boat ride to the nearest hospital. Luckily, there are a few programs that have been put into place to get a boat that’ll go to that part of the island and help people in situations like that. I believe the woman and the kids made it, but it was thanks to one of those programs that they were able to get a boat.

BS: That’s fucked up. Especially when a resort like Red Frog has so many resources. To not offer any kind of medical assistance, or even to donate some lousy dingy, at the least.

DE: Right, they could’ve just jetted over to the hospital, no problem. When people and tourism and hospitality companies ignore the need to make stuff like that sustainable, and when they think only in the short-term profit and not the long-term well-being of everyone, you get fucked up situations like that. Luckily, there are people out there who want to fix situations like that. It’s not easy.

BS: There’s plenty of resources to do it.

DE: It’s endless. If you sold one of those yachts in that marina, which looks straight at the village, you could give them health care.

BS: Seems like a pretty cathartic experience.

DE: It’s definitely eye-opening. It’s also crazy looking into the history of those people [the Ngobe tribe], and finding out they were one of the only tribes that defeated Columbus. The area was among the first places he landed and attempted to colonize, and the Ngobe basically just fucked them up for seven years until they left. They know that jungle better than anyone could, and Columbus just didn’t stand a chance. I spent so much time walking through the jungle with them, and they’d just point and say, check out that crocodile! Check out that sloth! Don’t step on this poisonous frog! And you’re just like, holy shit, I didn’t even see that.

BS: They’ve inherited generations of that wisdom.

DE: I think we tend to look at indigenous people as a kind of novelty, or something kitsch, like let’s go camping out in a teepee, let’s use their culture instead of appreciating it. Truth is they’re educated in certain aspects than a lot of people you’ll ever meet. I learned about their language [Ngäbere], which is dying out, and it shouldn’t.

BS: Are there recordings of it?

DE: I haven’t found any. Some of the older people’s first language was Ngäbere, and then they get taught Spanish, the national language down there, and just speak that the rest of their lives. You can catch conversations in the old language around the village, but none of the kids know it. And for me that was a real bummer, I was trying to tell them to keep it going, don’t let your language die out. It’s a beautiful language.

BS: Do you feel the same excitement coming back and shooting shows?

DE: Yeah, I feel like I got the spark back. I’m shooting my first show back tonight [Nick Waterhouse at the Bootleg with openers The Buttertones]. I want to try out some new things.

BS: Are you doing any festivals this year?

DE: I had the chance to do SXSW, but I did it last year. I’m trying to stay away from things I’ve already done. I’m actually planning on going to Europe this summer, and shooting a lot of bands out there. There’s a festival in Iceland I really want to do.

BS: European fests always have the sickest line-ups.

DE: I’ve been around L.A. long enough to have shot every local band I like. I really want to check out the scenes in Europe, Australia, Japan has really amazing live music too.

BS: Are you going to be shooting for anyone in particular?

DE: Just shooting for myself really. I have a few zines coming out that’ll be at Long Beach Zine Fest. My goal is to put together a real book of shows from around the world, including my experience in Panama.

BS: How were you treated down there, by the way, as an American?

DE: I noticed foreigners from places like Australia and Europe really care about this election. When people learned I was American, the first question was always, who are you voting for? It was interesting hearing different points of view from all over, especially Germans who travel a lot. There were a lot of them down there. It was also interesting to me that there weren’t a lot of Americans.

BS: We really don’t use our passports too much, do we?

DE: It wasn’t always that way up until recently. We’re just scared shitless. I was in Panama during the whole Zika virus scare, but no one down there gave a shit about Zika. Nobody was worried, and every American down there was terrified. The locals were almost laughing, like, what are you so scared of? Of course it’s a terrible thing, but there are so many more dangerous things down there that can fuck you up.

BS: So what did the Germans have to say about us?

DE: The general consensus was pretty much the same [laughs]. I got a lot of eye rolls, and a lot of, wow, your country’s fucked. They urged me: don’t do it, don’t vote for Trump—we’ve seen it happen before. It’s definitely going to be scary to see where this election goes.

BS: It’s certainly the craziest election. We’re showing our true colors. I try not to worry either way.

DE: Even if America is ‘over,’ we can still be great. Like I said, it could be so much worse. We have a lot here to keep us going.

BS: Some of the best culture came out of a once dirty, bankrupt New York City.

DE: Exactly. Maybe if we get a Trump presidency, Fugazi will reunite in protest on the White House lawn, and I’ll be there.

BS: It’s also a lot harder for politicians to bullshit us now. Without the internet, it would’ve taken us years to figure out who bought Hillary off.

DE: That’s what’s good about the technology, all that information can come at the click of a button. There’s nothing to hide behind anymore.

BS: Embracing this tech is great, but it’s also revealing a new culture to us we’re still trying to figure out. It’ll involve a lot of reevaluation.

DE: That’s why it was so refreshing living on an island in the middle of the ocean, and just getting back to the basics of survival. You walk through the jungle, and you collect your food. You go fishing, you catch a fish, and you cook it. You eat healthy and you go to sleep when the sun goes down. You wake up, walk outside and it’s just you, the island, and the community—and that’s as basic as it gets. The kids run around outside all day long, sun up until sun down, and that’s how they learn. You can see them learning in everything they do. Learning how to catch food for their family, learning how to talk and interact with each other, learning how to play soccer, learning to not touch this dog because this dog will bite you. It was really refreshing for me. I had to go outside to make a friend. Maybe you do have to watch your back in the jungle, but it’s also different over there. There isn’t this sense of laws or protection.

BS: Is there crime?

DE: Yes, and the shitty thing is a lot of it stems from tourism and outsiders. Cocaine is huge on the island because, guess what, gringos love cocaine. It’s very easy to make down there, and it’s very affordable for gringos, and it’s a way for locals to make money. There’s a whole demographic of tourists who come and do drugs in the middle of nowhere however long they want. So that happens, and the drug dealing is of course illegal there, so you’re just creating criminal after criminal merely out of demand. There’s also situations where tourists get robbed because they’re bring expensive computers and cameras, and there’s really no remorse from the natives doing it because those tourists are basically walking wallets to them. They’re not contributing to the community; they’re not leaving anything, just taking. That’s what the Red Frog resort is doing, just taking and not giving back, and that creates a lot of distrust. But if you go there with a mission, and try to make the community more functional, sure, you still take some, but you also leave something in your wake, and you can see the respect that those people have for organizations like Give and Surf.

Photos: David Evanko